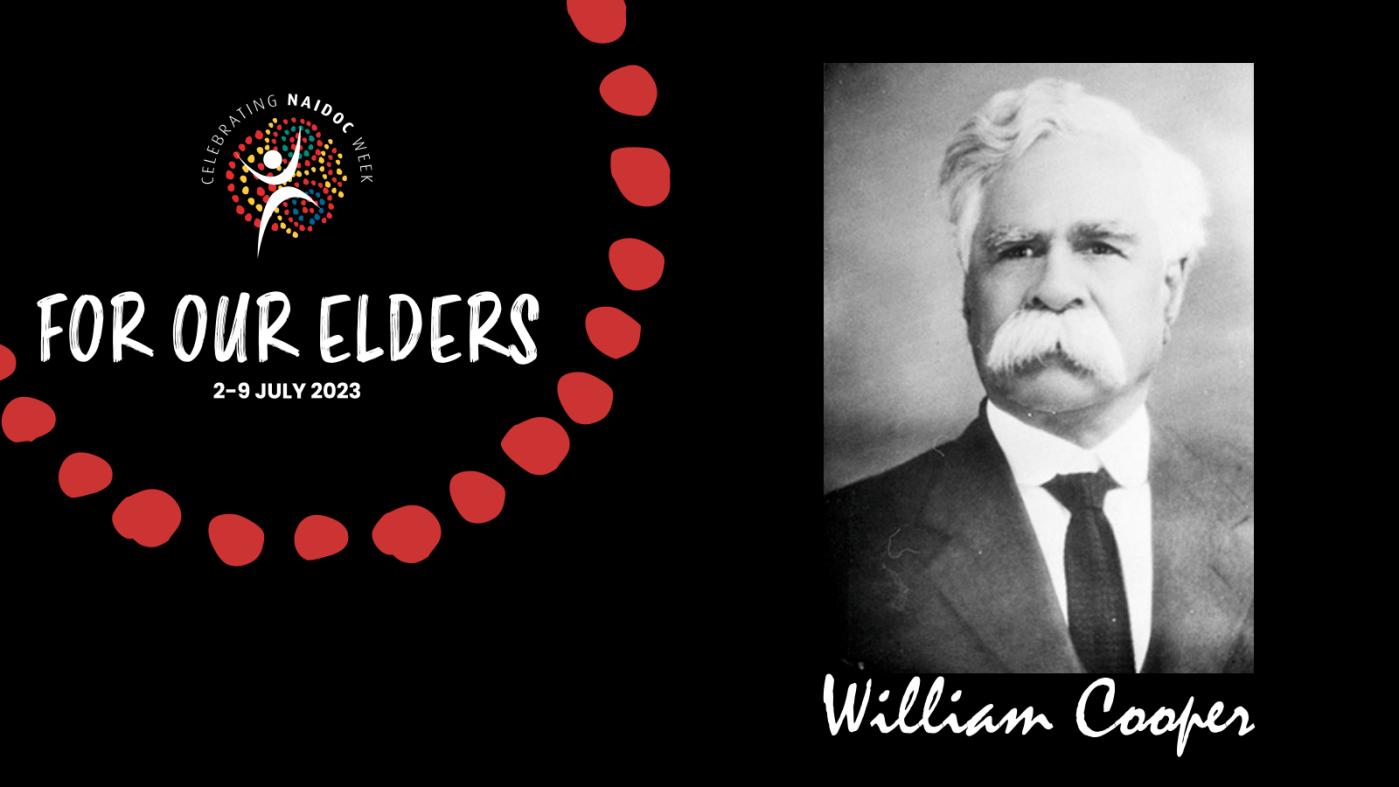

The theme for NAIDOC Week 2023 is ‘For our Elders’ so it’s a good time to introduce you to a very significant Aboriginal Christian Elder, William Cooper.

On December 6, 1938, the Consul General to the Third Reich, Dr Drechsler, received a deputation. A dozen men and women had marched from Footscray to Collins Street to object to “the cruel persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi Government of Germany and asking that this persecution be brought to an end.”

It was just weeks after Kristallnacht, that terrible night when Hitler’s henchmen had stormed through the streets of Germany smashing windows, looting and burning Jewish stores, and murdering some 100 Jewish people and detaining another 30,000 to be sent to concentration camps. As the news from Europe trickled through, these protesters decided to march.

They weren’t Jewish, but Christian. They weren’t German nor even citizens of their own country, but they had a heart for the persecuted citizens of another. And they were one of very few protests against the Third Reich at the time.

Who were these people? A group of Aboriginal men and women, led by 78-year-old William Cooper from Bangerang country.

Cooper knew what it was to be persecuted. He was born in or around 1860, already dispossessed: for the lands of the Yorta Yorta nation were already under the control of whitefella colonizers, and so was he. As he grew, he became one of many workers ‘forcibly retained’ (read: enslaved) by white station owners, and was shunted around wherever workers were needed. For many years he had little freedom of movement, and his wages were denied and unpaid. Around him, white landowners professed to be Christian even as they were said to go blackfella hunting after church on Sundays.

Yet one of the stories brought by the whitefellas galvanized Cooper: the story of Exodus. He recognized the cruelty of the Egyptian slavedrivers in the actions of white landowners, and Moses’ words to Pharaoh, ‘Let my people go!’ rang loud and true. So in 1884, Cooper was baptized and began his life’s work of demanding freedom both for his own people and for others.

An early step was the 1887 Maloga Petition, addressed to the Governor of New South Wales. Prepared one hundred years before Mabo, the petition stated that Aborigines of the district “should be granted sections of land not less than 100 acres per family … always bearing in mind that the Aborigines were the former occupiers of the land.” Needless to say, the petition did not lead to an immediate recognition of native title.

In 1935, he helped establish the Australian Aborigines League, and led efforts pushing for direct parliamentary representation, and voting and land rights. Recognizing that, although Aboriginal and Islander peoples were not granted citizenship of Australia they were nevertheless British subjects, he prepared a petition to go all the way to King George V. In it, Cooper argued that, by stealing land and denying legal status, colonizers had failed to uphold their duty to care for the original occupants. Unsurprisingly perhaps, the Commonwealth claimed a constitutional technicality and refused to pass the petition on to the king.

In 1938, Cooper joined forces with other Aboriginal leaders to establish a Day of Mourning. This was held on Australia Day to mark 150 years of colonization. It has since morphed, first, to Aboriginal Sunday, marked by the churches in the week before Australia Day each year, and also to the first Sunday in July, kicking off NAIDOC Week.

It is embarrassing that NAIDOC Week is observed by secular schools and governments yet so many churches ignore it: for it began as a direct call to the churches. Cooper specifically asked that churches recognize this day and preach on the situation of Aboriginal people, the issues they face, and their need of the gospel—perhaps because the stories of Exodus and the gospel planted the seeds of his own resistance.

The march on the German consulate in 1938 reflected this. The Yorta Yorta had identified with the dispossessed Jews of Exodus, and sought to draw parallels between their experience and that of the Jewish peoples. As Cooper wrote to the federal government soon after the march, “We feel that while we are all indignant over Hitler’s treatment of the Jews, we are getting the same treatment here and we would like this fact duly considered.” Needless to say, such a call was unheeded—just as the marchers themselves were not admitted to the consulate and their letter simply passed on to a security guard.

Indeed, as is true of much justice work, many of his actions looked futile at the time, and little that he campaigned for came about while he was alive. Yet Cooper showed how stories of faith can be embodied in each historic moment, and can catalyze demands for justice. His work paved the way for the next generation of Aboriginal activists, including his mentee Pastor Sir Doug Nicholls, and it continues to ripple through our society today.

So the next time you catch the train to Melbourne and go through Footscray, pause for a moment and remember William Cooper: for the footbridge at the Footscray Railway Station is named after him. He is also honoured by various Jewish Museums, including by the establishment of the Chair for the Study of Resistance during the Holocaust at Yad Vashem, the International Institute for Holocaust Research based in Jerusalem. You will find his statue in the Queen’s Gardens in Shepparton, and his name on the William Cooper Justice Centre in Melbourne. In 2018, the AEC renamed the Division of Batman to the Division of Cooper in his honour.

Let us hope and pray that these memorials help us go well beyond lip service, and that William Cooper’s holy imagining of equal opportunity before the law and direct representation in Parliament (now proposed as Voice) may soon become our reality.

Shalom,

Alison

Emailed to Sanctuary 5 July 2023 © Alison Sampson, 2023. Sanctuary is based on Peek Whurrong country. Acknowledgement of country here. The National NAIDOC logo is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-N4 4.0). This piece is heavily indebted to https://www.commongrace.org.au/william_cooper, and also draws from https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cooper-william-5773, https://www.firstpeoplesrelations.vic.gov.au/william-cooper, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Cooper_(Aboriginal_Australian), https://issuu.com/jhc_comms/docs/centrenews_centrenews_2011_issue1_1_/s/22061722 and https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/postcolonial-blog/2021/oct/31/the-extraordinary-aboriginal-leader-whose-story-the-australian-war-memorial-should-be-telling. The language used in this piece reflects the language used by William Cooper in the documents of the time.