The story of exodus points to the joy-filled possibilities of civil disobedience. (Listen.)

Have you heard of the Singing Revolution? Day after day, Estonians gathered to raise their outlawed flag, sing their national songs, and peacefully protest Russia’s violent occupation. After five years, a million people were regularly gathering and singing, such a vast, joy-filled experience I can barely imagine it: and eventually, the Russians left.

Political scientist Erica Chenoweth has found that just 3.5% of a population needs to be passionately engaged for a movement to achieve a groundswell and be successful; and that non-violent campaigns are twice as likely to achieve their goal. Other research shows that, for systems change, just 10% of people in the system need to adopt a change for it to be rapidly accepted. But if you don’t have that, they find, just get a small, committed group into a room, then let the energy expand outwards. Change will cascade through social connections and non-linear growth. The movement in Estonia started with a determined few, peacefully and powerfully singing: but as it gathered steam, the movement grew and grew.

I worry about Voice, and I worry about climate; and I know I’m not alone. But I recently learned that if just 10% of those who plan to vote Yes were to talk with a couple of Undecideds through their fears and help them move to Yes, the Voice would easily pass. And if just 3.5% of the population were passionate about climate action, the necessary changes would become not only possible but inevitable. All it takes is for committed people to show up, share ideas, and let the energy flow.

All of this is interesting to me. It is interesting because much of what we hear suggests that the people in charge make all the real decisions and hold all the real power. And I don’t deny that our leaders often do make decisions which have terrible far-reaching consequences, and they often do wield power in horrific ways. You only have to look at the disastrous fossil fuel projects which are currently being greenlighted, or the racist fearmongering around the Voice referendum, to see the truth of this.

And yet, this is not the whole story; and it’s certainly not God’s story. Instead, God’s story goes like this:

Once upon a time, there was a new story. A story in which people were oppressed. They were displaced from their homeland. They worked in cruel conditions for no wages; their children were being removed and even killed. A nameless pharaoh made their lives harder and harder: but God heard their cries.

Understand this: Back then, everyone thought your fate was divinely-ordained, inevitable, inescapable, and that power was a sign of divinity. Everyone believed Pharaoh was god. Everyone knew the oppressed were scum: their situation was evidence of this. And yet, God heard the cries of the oppressed, and things changed.

This is the radical newness in the story of Exodus, that Biblical epic in which God sets people free: God cares for oppressed people, and makes things change. More precisely, in an intensely hierarchical, patriarchal and racist society, God works among people at the intersection of the lowliest of the low, foreigners, women, children, and slaves, and uses them to bring this change about. Because this is where the real action of Exodus takes place: among a small group of people at the bottom of the heap.

How does it go? A nameless despot wants to consolidate his power. So he spins a tale that the foreigners are a threat and may turn against their hosts; then he enslaves them and sets them to hard labour on his egotistical building projects. And when that doesn’t ease his fear, because nothing ever will, he brings in the foreign midwives, Shiphrah and Puah, and tells them to kill every boy as he is born.

And right away we hear echoes of the slave trade, and of border walls, and of forced sterilisations; right away, we think of child removal and forced assimilation; right away, we know this story.

But the midwives know their story, too; they know their culture. They know that God is more important than Pharaoh; they know that life is God-gifted, sacred. So they band together and engage in a spot of civil disobedience. That is, they quietly let the babies live, and perhaps they encourage other midwives to do likewise; and they explain the living babies to Pharaoh by quoting his racism right back at him: ‘Those Hebrew women are nothing like delicate, feminine Egyptian women. Instead, they give birth like animals. They just pop the babies out before we get there.’

Well, Plan A being unsuccessful, Pharaoh moves to Plan B. He orders all the baby boys to be thrown into the river. And while many people comply, because fear makes people do terrible things, others engage in further civil disobedience. A woman named Jochebed makes a little ark. She gently places her baby in it and puts him into the river among the reeds. So she’s following Pharaoh’s order, yet completing subverting it.

Then in an outrageous plot twist, Pharaoh’s own daughter sees the baby and fishes him out. The baby’s sister Miriam just happens to be hovering, so she negotiates with Miriam such that the baby’s own mother is paid to become his wet nurse; and I imagine this came about because Jochebed, Miriam and their newfound ally, Pharaoh’s daughter, sat around plotting how to protect this little scrap of life.

And as we all know, after many years, the little scrap becomes a complex, stuttering man who continues the project which saved his own life. With God’s help, and the elders of Israel, and his brother, and finally an invisible growing groundswell behind him, Moses publicly and peacefully protests the slavery of his people and leads them into freedom.

We all know the big men, whether pharaohs, presidents, prime ministers or premiers; we are constantly bombarded by their names, images, and propaganda. We are conditioned to believe that they set the agenda, that they shape culture, and that what they say is the way things are and must always be. Climate change? Doesn’t exist—and is inevitable anyway. Sustainably logged native forests? It’s a thing—and jobs depend on it. Fracking? Necessary. Sweatshops? Unavoidable. Birthing trees? Unimportant. Destruction of culture? Regrettable. Institutional abuse? Impossible. The list goes on. And these lies are told to shape our reality, to teach us not to hope or dream, and to keep the powerless in their place.

But we are part of a different story, a story which stretches back to Exodus. And our story says, Pharaoh is not god, nor is any president, prime minister or premier. Our story says, power is no evidence of God’s favour or God’s gift. Our story says, God hears the cries of the oppressed, and God cares. And when God cares, then all is not hopeless and we are not helpless: as long as ordinary people remember their story and dare to live it out.

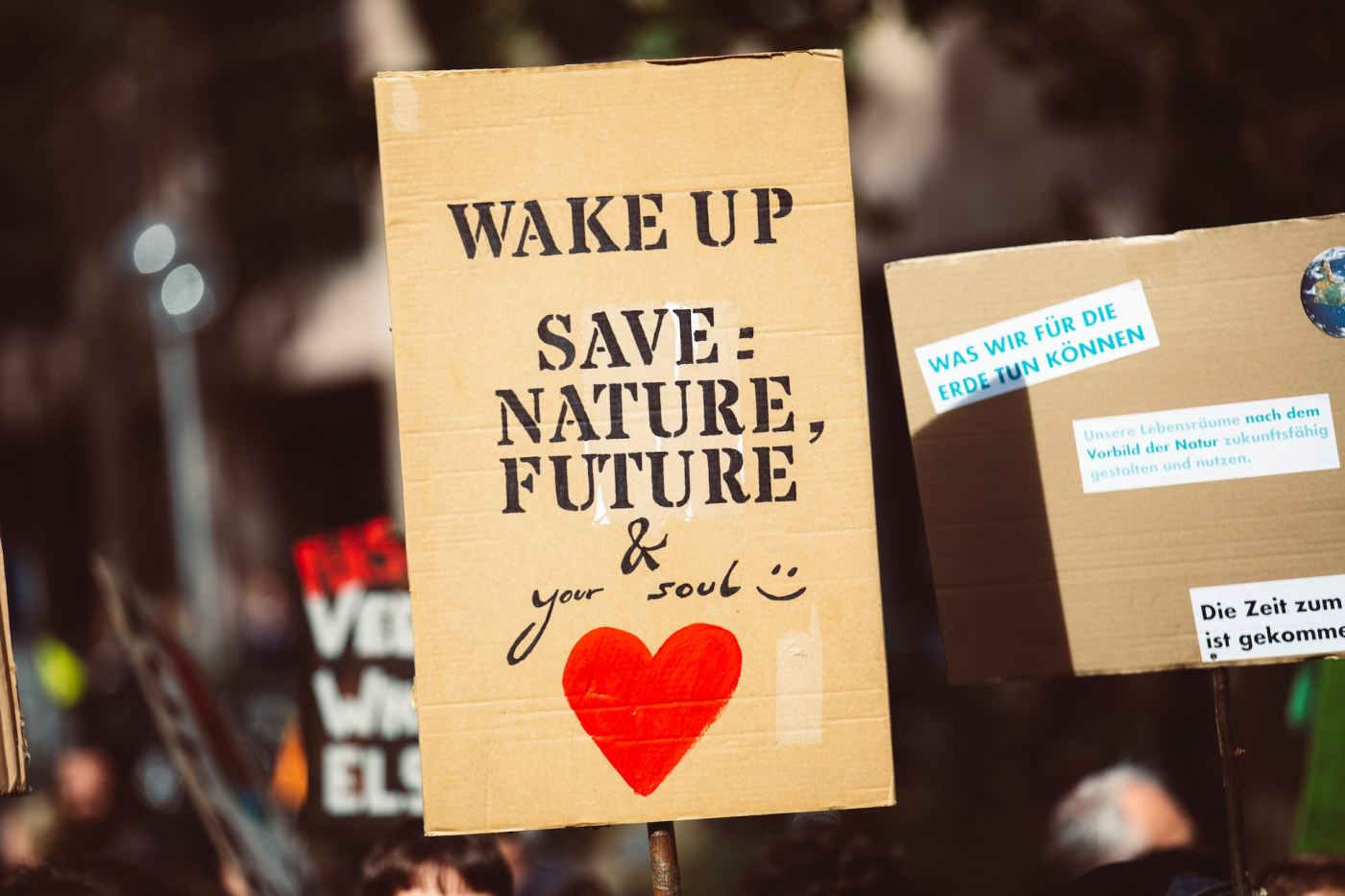

Thinking about how this plays out for us here and now, I don’t know whether #fightforthebight will be successful. Maybe seismic testing will continue: but I know it is less likely if the people against it keep showing up. Similarly, I don’t know whether #SchoolStrike4Climate or #LoveMakesAWay or #BlackLivesMatter or even Voice will achieve their goals in our lifetimes. But they’re taking the conversation forward in important ways, and if people keep showing up, climate health and justice for people seeking asylum and nonviolent policing and a meaningful Voice to Parliament will one day be inevitable.

And I also know this: God hears the cries of the oppressed, and God cares. And if we are faithful to our story, then, like Shiphrah and Puah and Jochebed and Miriam and even Pharaoh’s own daughter, in the face of great evil we must act. We must trust the Spirit more than social norms; follow God’s law more closely than human laws; and choose life and love over our personal comfort and even safety at times. Like the Estonians, we must sing in the face of violence and disrupt the forces of death; like the women at the River Nile, we must protect little scraps of life; like the midwives, we must talk back to power in wise and foolish ways if ever we are called to account.

For all of us are invited to be actors in God’s great story of salvation, which stretches across time and space. And when we are on the side of life and love and truth and justice and spirit and the communion of all things, then we can be confident that we are on the side that is already victorious, even when the victory cannot yet be seen. The struggle continues: but through Christ life and love have already won, and the forces of apathy, death and destruction shall not control us nor cause us to back down or fear.

So let us keep participating in God’s own story through Warrnambool for Yes! or Fight for the Bight or however else we are called; and let us be in on the victory as we gather with others to protect life in all its forms. For we worship the Creator, Breath and Word of Life: and this work is our spiritual worship. God’s will be done, God’s love be shown. Amen. Ω

Reflect: What is one way you engage with others to challenge evil and protect life? Do you sense an invitation to a next step, either for yourself or through you to others?

Acknowledgements: The title comes from the song, God make us agents of joyful rebellion, by David Bjorlin. He writes, ‘This text came after listening to an interview with Martin Sheen on the NPR show On Being. In it, he talked about the joy and life he experienced when he engaged in public protests. I began thinking about ways we could use joy as a tool of resistance and this was the result.’ Find it here. See also David Robson. The ‘3.5% rule’: How a small minority can change the world. 14 May 2019, found here, and Greg Satell. To implement change, you don’t need to convince everyone at once. Harvard Business Review. 11 May 2023, found here.

A reflection by Alison Sampson on Exodus 1:8-2:10 with a nod to Romans 12:1-8, given to Sanctuary on 27 August 2023 © Alison Sampson 2023 (Year A Proper 16). Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash.