Fear is immobilising, but Jesus’ peace offers a way forward. A reflection given to the good folk at Ashburton Baptist Church on 7 April 2024. You can listen to a recording of it here.

So Donald Trump is now selling a Bible. ‘God bless the USA’ is embossed on the front cover, along with a flapping American flag. If he ever actually opened the book, he might stumble across the first letter of John, a beautifully tender letter of love. And he might find the words, ‘Perfect love casts out all fear.’

It’s a shame Donald hasn’t read it: because his life seems driven by fear. Fear of Mexicans, fear of Muslims, fear of women. Fear of gay, trans and non-binary folx. Fear of diminishment, fear of vulnerability, fear of transformation. Fear of losing. Fear of prison. It’s tempting to mock him, except that similar fears are rampant in Australia.

The church is shrinking, I hear. We need to bunker down and protect what’s left. I don’t have enough super, I hear. I need to double down and protect my assets. I’m not homophobic, I hear. But my marriage should is the only form that is God-ordained and God-sanctified. I’m not racist, I hear. But there’s nothing wrong with our policing, and those people should stop demanding special treatment.

Fear of change, fear of scarcity, fear of diversity, fear of truth. Fear is normal and it’s something we all experience, even disciples, even and maybe especially on the day of resurrection. For the story of the disciples huddled in a locked room happens on the very day that Mary Magdalene found an empty tomb and told them about it; the same day she encountered the Risen Christ and thought he was the gardener. (Maybe it was the dirt under his fingernails.)

How do Jesus’ disciples respond to the news? They gather in a room and lock all the doors, out of fear. Nobody going in; nobody coming out. It is to a scared and bunkered down group of people that Jesus appears, and it is into their fear he speaks. ‘Peace be with you!’ he says. Then he shows them his wounds, and the disciples recognise him with joy. Again, Jesus speaks peace to them: ‘Peace be with you.’ Then he commissions them to continue his work, and breathes on them, and invites them to receive the Holy Spirit, spirit and breath being the same word in Greek and always a choice in translation.

Eight days later, however, we find the disciples in the same place. Eight days later, they’re still in the room with the doors shut tight, only this time Thomas has slipped in. And it seems that although the disciples have told him about Jesus’ appearance, he cannot believe it.

Thomas usually gets a bad rap here: Doubting Thomas. Faithless Thomas. Tsk-tsk Thomas, you shoulda been more trusting. Which is pretty rough, because Thomas never doubts Jesus. His doubt is based on the witness of the disciples, and that seems more than fair.

For if their story is true, then eight days earlier their crucified teacher had appeared to them and commissioned them to go out and continue his work. Eight days earlier, they had been called to a life of blessing, forgiving, and sharing God’s peace—a life of joy! Eight days earlier, they had been invited to enter into the new creation: but they had opted to stay in a self-imposed lockdown. So whatever story they were telling Thomas, their lives communicated something different. Their lives communicated that nothing had happened, nothing had changed, and fear still ruled the day. And so, Thomas doubted.

But what were the disciples so afraid of? Why were they so immobilized by fear?

One reason, we are told by many translations, is ‘for fear of the Jews.’ Now, the gospel according to John is problematic, in that it can be misread as anti-Semitic. Christian supremacists erase its Jewishness and read these and similar verses as a critique of all Jewish people. They then use this to justify anti-Semitic behaviour. In fact, and very shamefully, there is a spike in anti-Semitic persecution and violence in Holy Week each year.

But everyone in the story is Jewish, and the disciples’ rabbi and beloved friend had just been executed by the state at the urging of their own religious hierarchy. They were first hand witnesses to the toxic relationship between religious and civil authorities; they saw how terror is used to control. Of course the disciples were afraid of the Jews, specifically those Jewish authorities who collaborated with empire.

They were afraid the way I am afraid of Christian nationalists who seek to control or erase brown, female and queer bodies, and who are moving towards fascism to achieve their goals. They were afraid the way I am afraid of evangelical pastors who support a cheating lying sexual predator, simply because he will appoint anti-abortion judges. They were afraid the way victim-survivors fear a Catholic hierarchy which made cosy arrangements with the police; they were afraid the way many Jewish people are afraid of Netanyahu and his cohort and their genocidal activities. The disciples were right, very right, to be afraid of the Jewish authorities.

But maybe they were also afraid of something else. Maybe they were afraid of Jesus. Maybe they were afraid to be seen by the one whom they had betrayed and denied and maybe they wondered, after all this time and all his teaching, if he would come to judge and destroy them.

Or maybe they were afraid of resurrection life and the strangeness and weirdness of it all. Maybe they had an inkling of what this life might look like and were terrified of the radical changes it might bring.

Whatever, fear is normal, and it’s something we all experience, even disciples, even and maybe especially on the day of resurrection.

But just as I am afraid and still Christian, the disciples were afraid and still Jewish; and when the Jewish rabbi Jesus offers peace to his terrified disciples, he is talking about a Jewish concept. This concept is shalom. And it is important enough that he says it three times. ‘Shalom,’ says Jesus. ‘Shalom, my friends,’ as he breathes his spirit into them.

Now, the gospel writer wrote this Jewish story down in the dominant language of the time, which was Greek, and we then translated it into English. So Jesus’ greeting of ‘shalom’ becomes the Greek ‘eirene’ becomes the English ‘peace.’ And on the way through, the thing we call peace picked up all sorts of smooth, Greco-Roman overtones.

So we hear ‘peace’ and think, Absence of conflict. We think, Everything’s fine, everyone’s cool, hippies, pot, flower children, whatever. If pressed, we might think about Gaza or Ukraine or some other far-off warzone where there is no peace. And then all too easily we turn the page. Because for many of us, I suspect, the story is so familiar, the words so bland, the peace so smooth, that it tends to wash over us. Just another resurrection story, tsk-tsk Thomas, here you are doubting again, peace, peace, yada yada yada—then it’s all over for another year. Because our notion of peace is too shallow, too thin; it doesn’t address the fear which rumbles along under our lives and every now and then erupts into violence.

If we go back to the Hebrew, however, we find something much more powerful. We find shalom. And what is this shalom offered to fearful people? Put simply, shalom is right and just relationship between God, people and the land; while sin is a disruption of this relationship, whether through negligence or violence. So right relationship is the gift which Jesus gives to his disciples: and it’s made possible through the further gift of the Holy Spirit.

For after he speaks peace and commissions them, Jesus breathes on them and invites them to receive the Holy Spirit. And all who know their Jewish scriptures are taken straight back to Genesis, when God’s breath swept over the face of the waters and spoke good things into being, and God’s breath filled the nostrils of the earth creature and made it truly live.

The writer is telling us that this is a story of a new creation. It began when Christ defeated death once and for all; it is found in a garden where God walks and speaks with a woman; it continues among disciples who receive the spirit of the crucified and risen Jesus; and it grows among all those blessed ones who have not seen, yet place their trust in Christ. Its hallmark is shalom, that is, right relationship between people, God and the land, and those who lean into it know faith and fullness of life. Which all sounds very nice in theory, but what does this mean in practice?

If we revert to the bland English ‘peace,’ then we might think in terms of absence. Absence of conflict. Absence of difficulty. Absence of complication. Or, more positively, we might think in terms of things being calm and pleasant: it’s all good. You see memes of this peace with puppies and flowers. For a nice English peace means fitting in. It’s about not standing up, not standing out, refusing to make waves. It’s receiving comfort at church, then going home and living like everyone else the rest of the week, only perhaps with a little more gentleness, a little more charity.

And if this is all we expect from peace, then we will find our churches shrinking and our giving mean-spirited and ourselves bunkering down, protecting our values and our assets. Whatever story we are telling, our lives will communicate that nothing has happened, nothing has changed, and fear still rules the day. And when we tell others about this faith they’ll just roll their eyes, like Thomas.

But if we open ourselves to shalom, this powerful idea of right living, if we inhale and savour God’s spirit-breath, then we will find ourselves smashing into presence. The presence of God. The presence of other people. The presence of country. The presence of sin and conflict and interpersonal relationships and all their challenges and difficulties.

And if we turn a page or two of our Bibles we won’t in fact find blandness but the Acts of the Apostles, a story about faith in action, erupting off the page. For it’s a story of people living with shalom and constantly smashing into presence. We find old Peter overcoming his deep visceral disgust to eat with Cornelius and his family. We find Philip overcoming a lifetime of conditioning that people with altered genitals cannot be holy, and baptising and commissioning an Ethiopian eunuch. We find disciples overcoming their fear and loathing of death to raise and touch the beloved Tabitha. And perhaps most surprising of all, we find rich people overcoming their fear of scarcity and letting go of their possessions so that others can thrive.

We find, and I quote Acts chapter 4 verses 32-35, that ‘the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common. With great power, the apostles gave their testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great grace was upon them all. There was not a needy person among them…’ So we find power and grace; we find love in action, and the evidence suggests that it indeed casts out fear.

This is what fullness of life looks like. A life no longer limited by fear. A life where we are no longer possessed by our possessions; a life not governed by shame.

Instead, as disciples we are called to a life of right relationship between God and people and the land: a new creation where lives intersect and strangers become friends and everyone is housed and fed. Shalom means no more envy, no more rivalry; status anxiety becomes a thing of the past. There is no more ‘us’ and ‘them,’ simply one heart, one soul, living with an economic justice which is powerful in testimony and overflowing with love and grace.

Fear of change, fear of scarcity, fear of diversity, fear of truth. Fear is normal and it’s something we all experience, even disciples, even and maybe especially on the day of resurrection: and I suggest to you that much of the church in Australia these days seems to be governed by fear. Clutching onto buildings. Protecting our assets. Hostile to change. Defining ourselves against others. Turning people away then slamming the doors, and wondering why life feels so pinched and mean.

But we are called to a different way, a bigger way, the way of shalom. And Jesus comes to the places where we are bunkered down in fear: to speak peace, to bless us, and to commission us.

My friends, today is the first day of the week: and every Sunday is the day of resurrection. Every Sunday, we are invited once more to receive the Holy Spirit. We can lock the doors, protect our assets, and define ourselves against the world. We can hold our breath tightly, so tightly, and live in this miasma of fear. Or we can open ourselves to presence and transformation, and imagine new life, new relationships, new economics, new possibilities—and let those imaginings change us.

Shalom, says Jesus. I send you, says Jesus. Receive the Holy Spirit.

All you need do is let everything go, then deeply, expectantly inhale.

Let us pray: Jesus, our Lord and our God,

when you rose from the dead

you came to your disciples.

You walked into their fear,

and offered peace.

You showed them your wounds,

and offered blessing.

You entrusted them with your work,

and offered life in all its fullness.

Help us move beyond fear and accept your gifts,

that we may be a blessing to others

and an embodiment of shalom,

that, through this powerful witness,

all may have life in your name. Amen. Ω

Reflect: What fears immobilise you? What is one small step you could take towards the new creation?

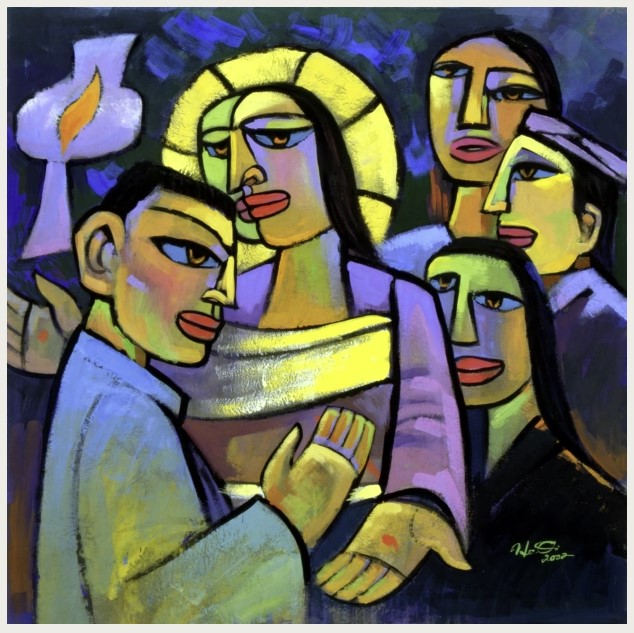

A reflection shared with Ashburton Baptist Church on 7 April 2024 (Year B Pascha 2) © Alison Sampson 2024. Image shows James He Qi. The Doubt of St Thomas (2014). This reflection was prepared on the lands of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation.