A reflection on baptism, shared with Coburg Uniting Church. (Listen to a really terrible recording here.)

I am a Baptist, which means I have a hearty appreciation for believers baptism. So hearty, that I was 25 before I felt remotely ready to take the plunge. Given many of you were christened as infants and confirmed as tweens, I’d feel slightly embarrassed telling you how old I was, except that Jesus was thought to be about 30 when he turned up on the banks of the Jordan.

His baptism was a ripper: heavens tearing open, a spirit-bird, a voice like thunder. Mine, on the other hand, was pretty rubbish.

For me there was no River Jordan, just a dented tub in an ugly room. Our church at that time met in an old reception centre. We didn’t have a baptistry, and Melbourne’s inner city waterways are not good places to go sticking your head underwater. So two deacons were sent to another church to borrow a portable baptistry: a corrugated steel half tank. They threw it in the back of a ute, then headed back to the inner city. As they were hooning down the Eastern Freeway, the tank flew up and bounced off, narrowly missing speeding cars.

‘How could this be?’ we asked when they finally turned up, sheepishly carting the now dented tub. ‘It was heavy,’ they said defensively, ‘We didn’t think it needed tying down.’

For baptismal preparation there was no hairy prophet, but a smooth-skinned man who told me to read Tillich first. I hated Tillich. The ideas and abstractions echoed round my skull, signifying nothing. They seemed completely unrelated to what I was doing, written in a language I couldn’t comprehend.

On the day itself, God’s voice didn’t thunder. The heavens stayed resolutely shut. Not even a small bird floated down from the skies. Instead, I got told off by a woman for wearing a plum-coloured shirt. ‘It should have been white,’ she said.

Coming up from the waters I felt silly, adolescent, awkward, strange, no more sure of God’s love or my direction or my self. And my mum was still dying and I still hated my job and I still had no idea how to live in this world. I had so wanted that dove floating down from the sky; I longed for the grand epiphany. Instead I came up from the waters self-conscious, dripping wet, thinking nothing much had happened after all.

It could have been worse. A friend of mine was baptised with similar hopes at a similar age. She tells me there is an embarrassing photo of her emerging from the waters with a sanctimonious expression on her face, eyes raised piously heavenwards. Thirty seconds later, she realised she had forgotten her towel. But like Arthur Dent in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, I had my towel with me. I was ready for something, anything to happen, maybe even to explore the universe, and baptism-with-towel had seemed like a good first step.

It’s a pity it felt so meh. But I didn’t really have a clue what I was doing. God didn’t seem very real to me, and Tillich wasn’t any help. I just had a hunch that baptism was a door into a mystery I was wanting to explore. I also knew that baptism is something John offered, and something Jesus underwent, and something his disciples are told to do. I knew that, in the Bible, it’s something offered to individuals and households and adults and babies; and in churches these days, ditto. I knew that it had something to do with water and washing and sin and death: but what, really, is it? What are we doing, what are we declaring, who are we becoming when we are baptised? Tonight’s story offers a few clues, but to explore the depths, we’ll first need to zoom out.

There’s a Jewish practice called mikvah, which involves taking a ritual bath to purify oneself for worship and for engagement with the wider community. Menstruation, sex, tending to a sick person and many other things call for mikvah: and every mikvah bath contains some living, or running, water. In today’s story we see that John took this practice and rewilded it. He took it out of the ritual bathhouse and down to the river, where the water was deep and the current flowed. There in the Jordan, he called people to wash away their sin and to enter into a ritual death and rebirth.

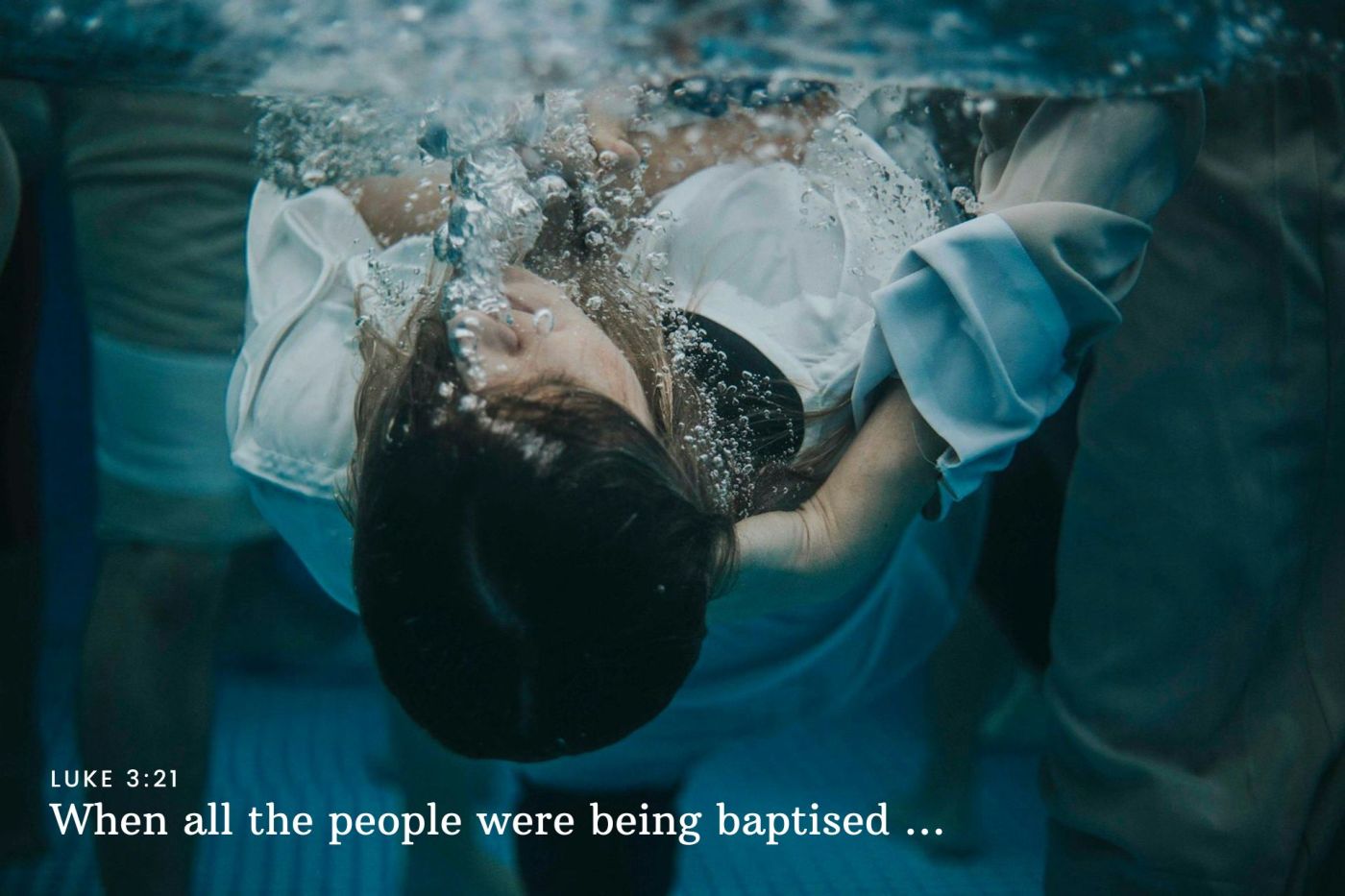

John’s focus was not on external pollutants, but internal. It seems he wasn’t so fussed by blood, pus and semen, but by the drives which lead us to destruction. So he plunged people into the waters to symbolise entering the grave. In the murky dark, breathless, the old self died and with it its ordinary ways of being and doing. Grasping, avenging, hating, harming, dominating, rivalling and other pollutants were washed away.

Coming up from the waters, the newly baptised were born again into the wildness and goodness and sacredness of a world where everything and everyone are connected. The perceived barriers between people and plant, river and rock were gone: for in God’s reality, all things are reconciled. Washed, reborn, integrated into God’s reality, the newly baptised were ready to live differently.

What did this difference look like? John exhorted the people to embody God’s reconciled reality in their lives. He told them to share what they have: ‘If you have two coats, give away one.’ He told them to take only what they need: ‘If you are a soldier, be content with your wages.’ He told them to resist the economics, politics and violence of empire, and he spoke truth to power. It was heady stuff and the crowds loved it: but it led to John’s arrest. And it is only now in Luke’s account that we get to Jesus’ baptism.

So Luke opens his story by listing the powers that be. Then he shifts focus to the rabble far from the centres of power who are engaging in John’s anarchic rewilded religious ritual. He notes that John is arrested for speaking truth to power. Finally he tells us that, along with all the other people, Jesus is baptised.

What we should notice is that baptism occurs in the midst of life. Jesus is standing in line with all the other sinners, not separate from but among them. And I’m sure there were a couple of men there, somewhat inept and defensive, and a bloke who loved good theology, and a woman who thought Jesus was wearing the wrong clothes, and a bunch of clueless converts like me who were giving this thing a go, and even one or two who had forgotten a towel. Because according to Luke, ‘all the people’ were there: sinners, tax collectors, people like us.

More, all around John, Jesus and the rabble seeking baptism seethes the chaos and violence of empire; they cannot escape it. Kings arrest holy men; Roman soldiers rape and pillage; taxes cripple the countryside; debt slaves are hauled off to market. Forests are razed to build war machines; land is made desert. Poor, sick, broken, messy people are excluded from institutional religious life: for some physical markers cannot be washed away. And in the midst of all this, the people are baptised including Jesus, Emmanuel, God-with-us.

Luke’s structure shows us that baptism isn’t a free pass on this life. It’s not a ticket to heaven, nor is it a way to avoid trouble. It’s not separate from other people, and it’s not separate from oppression and pain. Instead, it’s an invitation to incarnate heaven here and now, in the midst of things among ordinary people who are struggling with the conditions of their lives.

So that’s baptism in general, but Jesus’ baptism (by whom we don’t here know) has some interesting details: the dove, and the slightly odd phrase, ‘the Beloved.’ The dove is an allusion to the story of Noah when, towards the end of his ordeal, Noah releases a dove. It returns with an olive branch and with it the message that the flood waters are receding; there is a new creation; life is beginning again.

The second detail may refer to Psalm 2, where the Beloved is a king called to save God’s people from the raging violence of the surrounding nations. It may also refer to Isaiah 42, where the Beloved is the Suffering Servant: the messiah called to save the people from their sin and suffering, but only at the Servant’s great personal cost.

These signs in the baptismal story are both warning and promise. They reinforce the theme that baptism happens in the midst of life, under systems we cannot control. They make it clear that being God’s Beloved is no protection against suffering and may even lead to it. Yet whatever happens, the dove declares that all will be well and all will be well and life will begin again. God’s love will endure through everything, even violence, even suffering, even death; and here we have Jesus’ life, death and resurrection in a nutshell. And because there is only one Lord, one faith, one baptism (Ephesians 4:5), this is our baptism and our life, too.

So those of us who are baptised are called to live like Jesus, even at the risk of great personal cost. Just as he went down to the river to align himself with sinners, soldiers and tax collectors, we too are called to align ourselves with those who cannot avoid the world’s injustice. And just as Jesus’ resistance to temptation and his preaching, teaching and healing flowed out of his baptism, so too are our lives shaped by our baptismal commitments. For in the wildness and goodness and sacredness of a world where everything and everyone are connected, the barriers between people and plant, river and rock are gone. In God’s reality, all things are reconciled. The violence and horror of empire is unmasked, and business as usual is no longer an option. Instead,

- In place of rapacious consumption, we are called to simplicity and sharing.

- In place of patriarchal violence, we are called to mutuality and gentleness.

- In place of retaliation and warmongering, we are called to peace-making and enemy-love.

- In place of an extractive economy and environmental destruction, we are called to delight in and serve the earth.

- In place of atomisation and self-reliance, we are called into the community of Christ.

- In place of trust in money, we are called to trust in God.

No matter what the world throws at us, and there will be plenty, these are the commitments of the baptised. I didn’t realise this at the time of my own baptism, and I struggle to embody these commitments now, yet they describe our life’s trajectory.

So, given my naivety, even ignorance, and given the absence of any hyper-holy cosmic experience, was my baptism rubbish? Well, if I only look at the line about Jesus’ baptism, then yes, it was a bit crap. But if I set it in the wider context of Luke’s story, then I dare say my baptism was enough. For it was conducted among the sinners and saints of an ordinary church, rather like the rabble down at the Jordan. It wasn’t a free pass on life’s struggles, but it gave me a way of reframing them. It was a death of sorts, including of some of my illusions and expectations. With this death came a long slow rebirth into a new way of life: a way of being grounded in this ordinary troubled world, a way of resistance to violent structures, a way of belonging to a fragile community, a way of relationship with God and people, river and rock, a way which continues to unfold even now.

So my baptism is the moment I look back on when, like Mary at the annunciation and like all the people at the Jordan, I offered my ‘Yes’ to God. And despite the absence of birds or a voice like thunder, and despite my ongoing wrestling, questioning, doubting and stumbling, it’s been shaping my life, the universe and everything ever since. Ω

Intriguingly, as we sang our final blessing, a magpie flew past in a long gentle swoop, framed by the large picture windows.

PS – If you are horrified by John’s language of winnowing people out and burning the chaff, read this.

A reflection on Luke 3:15-22 shared with Coburg Uniting Church on 12 January 2025 (Year C Epiphany 1) © Alison Sampson 2024. Photo by Marcos Paulo Prado on Unsplash (edited).